source: disturbingtheuniverse.com

source: disturbingtheuniverse.com

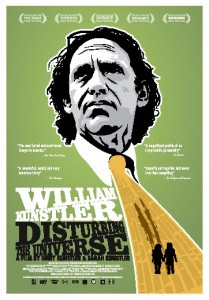

From the film’s website: In William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe filmmakers Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler explore the life of their father, the late radical civil rights lawyer. In the 1960s and 70s, Kunstler fought for civil rights with Martin Luther King Jr. and represented the famed “Chicago 8” activists who protested the Vietnam War. When the inmates took over Attica prison, or when the American Indian Movement stood up to the federal government at Wounded Knee, they asked Kunstler to be their lawyer.

To his daughters, it seemed that he was at the center of everything important that had ever happened. But when they were growing up, Kunstler represented some of the most reviled members of society, including rapists and assassins. This powerful film not only recounts the historic causes that Kunstler fought for; it also reveals a man that even his own daughters did not always understand, a man who risked public outrage and the safety of his family so that justice could serve all.

About the Film

The film’s title comes from T. S. Eliot’s poem, The Love Song of Alfred J. Prufrock. At the end of his life, many of Kunstler’s speeches were entreaties to young people to have the courage to take action for change. He frequently spoke about Michelangelo’s statue of David as embodying the moment when a person must choose to stand up or to fade into the crowd and lead an unexceptional life. He also recited parts of Eliot’s poem, where Prufrock wonders if he “dare disturb the universe.”

“Sarah and I wanted to fit dad’s life into a single unified theory,” said Emily Kunstler when asked about what it was like making a documentary about her father William Kunstler, the radical civil rights attorney. “We wanted all of his clients to be innocent, and all of his cases to be battles for justice and freedom.”

That is how it had seemed when Kunstler fought for civil rights with Martin Luther King Jr., and represented the Chicago 8 who faced jail for protesting the Vietnam war. When inmates took over Attica prison, or Native Americans stood up to the federal government at Wounded Knee, they asked Kunstler to be their lawyer. To Emily and Sarah, he was a hero from legend, who stood at the center of everything important that had ever happened. “His clients were fighting to change the world, and he was fighting to keep them out of jail,” said Emily.

But the girls weren’t around for their father’s glory days. Born in the late 1970s when Kunstler was almost 60, the father they knew publicly kissed the cheek of a Mafia client and condoned assassinations he viewed as political. He represented an Islamic fundamentalist charged with murdering a rabbi, a terrorist accused of bombing the World Trade Center, and a teenager charged with participating in a near-fatal gang rape.

By the time Kunstler died in 1995, his teenage daughters thought he had “stopped standing for anything worth fighting for.” Once idolized, he had become an embattled, if still dazzling, loner.

“Dad moved himself to tears with his own grand speeches,” said Emily. “And the crazy thing was, it actually worked.” Defending a drug dealer, he won the first and only acquittal on self defense of person who shot at and wounded police officers.

Still, there was the legend of the extravagant hero who in 1960 had left his safe, suburban life and traveled south to join the civil rights struggle. There, Kunstler, whose own parents had black servants who ate in the kitchen and used separate toilets, “was reborn into a man I liked better,” he said, “one who contributed to society and tried to make a difference.”

Within a few years, Kunstler was catapulted into international fame when he defended the Chicago 8, protesters charged with inciting riots outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention. He defied the judge and put the Vietnam War and American racism on trial. But the trial changed Kunstler. He had once believed that the law was an instrument of justice. Now he saw a legal system that enabled “those in power to exercise social control” and “at all costs, to perpetuate themselves.”

Kunstler witnessed the power and the costs first-hand at Attica Prison when he was called in as a liaison for the inmates during the 1971 rebellion. The audience sees it, too, through devastating archival images that show what happened when state troopers stormed the prison, covered the yard with tear gas, and opened fire on the prisoners, killing 29 inmates and nine hostages and wounding hundreds. With clear eyes, the film addresses both the viciousness of the state and the charges that Kunstler did more harm than good by hardening the prisoners’ resolve and giving them unrealistic expectations of amnesty.

Throughout the film, in historical footage and compelling interviews, Kunstler’s critics, defenders, and clients talk about how one man made a difference. Some still hate him, some 5 credit him with saving their lives and freedom, others acknowledge that he irrevocably and improbably changed their view of race and politics. “That’s when I learned not to like my government, not to trust them,” said Jean Fritz, a Republican who had been a juror at the Chicago 8 trial and watched black defendant Bobby Seale chained and gagged. “And that’s hard to say, but that’s how I felt.”

A string of sensational trials and stunning victories fed Kunstler’s belief that because he was skilled, passionate, and right, he could convince anyone. But while that made him a great lawyer, it did not make him an easy father. “I remember pleading with him not to represent a teenager accused of a gang rape,” said Emily about Yusef Salaam, a black 15-year-old accused of participating in a savage attack on a female jogger in Central Park.

“I think dad always believed [Yusef Salaam] was innocent, but it was never about innocence for dad. He looked at Yusef and saw a kid who had been convicted by public opinion — and by his own daughters — before the case ever went to trial,” said Emily. The media, captivated by the case, ran headlines calling the accused “monsters.”

We see this “monster” years later, as a gentle and introspective adult who, it turns out, had been innocent all along, and was exonerated by DNA evidence after six and a half years in prison. Kunstler was right: It was racism and a biased legal system that had failed, and continues to.

Indeed, it is hard not to reassess his defense of despised “Muslim terrorists” in the light of post-9/11 violations of the rights of Islamic Americans.

“I suspect,” says Kunstler talking to a crowd during the Chicago 8 trial, that more people “have gone to their deaths through a legal system than through all the illegalities in the history of man: 6 million people in Europe during the Third Reich. Legal. Sacco and Vanzetti. Legal. The

hundreds of great trials throughout the South where black men were condemned to death. All legal. Jesus. Legal. Socrates. Legal. All tyrants learn that it is far better to do this thing through some semblance of legality than to do it without that pretense.”

And there is the heart of the film: Kunstler inspires by choosing justice over law and order, by defending pariahs because pariahs are most in need of defense, and by doing it all while grandstanding for the media.

In the end, viewers, along with his daughters, reconcile Kunstler’s uncomfortably complex parts into an all too human, all too familiar, whole. The film makes relevant to today the issues that were important to Kunstler: racism, freedom of speech and action, prisoners’ rights, anti-war

activism, and the encroachment of government power. With candor and affection, William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe illuminates the key civil rights battles of the 20th century through the life of one man who was a part of the fight for justice.

Director’s Statement

William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe grew out of conversations that Emily and I began having around our father and his impact on our lives. It was 2005, ten years after his death, and Hurricane Katrina has just shredded the veneer that covered racism in America.

Growing up, our parents had imbued us with a strong sense of personal responsibility. We, too, wanted to fight injustice; we just didn’t know what path to take. Even though I went to law school, I think both Emily and I were afraid of trying to live up to our father’s accomplishments.

It was in a small, dusty Texas town that we found our path. In 1999, an unlawful drug sting imprisoned more than 20 percent of Tulia’s African American population. The injustice of the incarcerations shocked us, and the fury and eloquence of family members left behind moved us beyond sympathy to action.

While our father lived in front of news cameras, we found our place behind the lens. Our film, Tulia, Texas, Scenes from the Drug War helped exonerate 46 people, and this sealed our fate as filmmakers.

One day, when we were driving around Tulia, hunting leads and interviews, Emily turned to me. “I think I could be happy doing this for the rest of my life,” she said, giving voice to something we had both been thinking. It was years later that we realized our father had made a similar journey to the South and left a trail of breadcrumbs we had unconsciously followed. The journey had changed his life as well.

When we decided to make a film about our father, we worried that the people we interviewed would see us only as Kunstler’s daughters. But rather than being an impediment, this inevitable framework became a strength. And we knew that many other children, especially those who were young when their parents died, take a similar adult journey toward reconciling the parent with the person.

Today, with the election of America’s first African American president, it is tempting to relegate the civil rights movement to a bygone chapter in a history book, and to celebrate our victories without acknowledging how much work remains. More than 50 years have passed since the Supreme Court ruled that separate schools for white and black children are inherently unequal.

Still today, racism and bigotry cast ugly shadows on our schools, streets, and courtrooms. Emily and I wanted to bring our father’s story, and the battles he was a part of, out of the past, and to remind audiences that freedom is a constant struggle, and that the people who fight for it are

heroes, not because they are without flaws, but because they see injustice and find the courage to act.

William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe is a film about and for people of courage. We hope that it communicates that the world we inherit is better because someone struggled for justice, and that those changes will survive only if we continue to fight.

— Sarah Kunstler, Director and Producer

0 Comments