Performance artist Monet Clark’s inspiring story

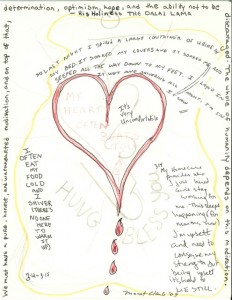

Poisoning/Phoenix Performance Document #5 © Monet Clark

(click image to enlarge)

How does one go from twelve years in a wheelchair and mostly bedridden – two of those years too weak to roll over or sit up or feed oneself – to walking, world traveling, working, and riding a bike? This is the inspirational story of Monet Clark, a performance artist who made art out of her experience with chronic environmental illness and continues to recover from severe chemical sensitivities today.

Monet’s story starts in January of 1992, when she had an adverse reaction to a vaccination she received before traveling to Asia. She developed silver blisters under the skin of her palms and couldn’t close her fists due to the pain. After this initial vaccine reaction, new symptoms continued to appear. Within nine months Monet was in a wheelchair and couldn’t walk across the room. At her worst, she looked like a Holocaust survivor, emaciated and on the verge of death, bedbound and unable to move.

She was diagnosed with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) soon after she became sick. She had all the symptoms and her lab tests came back negative for everything else. However, seven years into her ordeal, a new doctor found she had very high levels of mercury and arsenic in her body. Both are byproducts of mining and she grew up in an old Gold Rush boom town. Her family’s property was next to one of the “diggings,” which are huge excavation sites. Mercury was in their well water and in the river she would swim in as a young girl. She also learned that mercury is used as a preservative in vaccinations. Heavy metal toxicity seemed to play a big part in Monet’s health challenges.

Further tests conducted by other doctors indicated a viral issue was also part of the problem. Her current acupuncturists, who are highly skilled Chinese doctors, say they see many patients with autoimmune problems resulting from vaccinations, and their work focuses on rebalancing the immune system.

To recover her health, Monet ate nutrient-dense superfoods, tons of alkalizing green vegetables, seaweed – everything grown organically. She also ate organic meats. During this time, she researched, studied and used many different supplements, herbs, and homeopathic formulas that all that focused on cleansing and nourishing. She avoided all forms of sugar and sweet foods for many years. At one point she even took injections of animal organs from a renegade German physician. She also underwent intensive therapy including EMDR for trauma release – a practice that is used by veterans suffering from post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – and many forms of spiritual transformational practices, from Network Chiropractic, to Tibetan Buddhist pujas, to shamanism, yoga, mudra practices, and Reiki, to name a few.

At her worst, near death, Monet breathed love in and out of her heart chakra – a very cleansing practice which dissolved all negative thoughts and emotions into LOVE, forgiving everyone who had disbelieved, judged and abandoned her. At one point when she was near death she could feel herself getting too ill and creeping closer to death if she entertained hatred at her family for abandoning her or fear for her future. So she would use this breathing practice to shift these life-draining thoughts, bringing her focus back to love. In that energetic vibration she could feel herself get a little stronger, and she continued recharging herself like this until she pulled out of the near death state.

Love and forgiveness saved her life, as did faith. Monet says, “These are the keys that unlock the doors to the miracle realm where dramatic shifts are possible.”

Another important component of her healing journey: she never lost sight of her life post-illness; what she would do, how it would look. She always believed that she would get better and would visualize herself dancing when she couldn’t lift her arms. Monet knew she had more life to live.

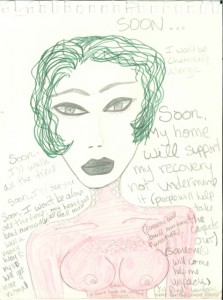

Throughout her entire ordeal, Monet turned to creative expression for both inspiration and as a means of validating and recording her experience. She made drawings that were filled with affirmations. She also conceptually “framed” her still photography work as performance art – the performance being her life and what she had to endure each day. She took a powerful mental and spiritual stance on her own survival, and worked hard to achieve it.

Monet shares, “Releasing trauma and fear are very important, as is faith and focusing on what progress you made, the joys in your life, and NOT the illness and the symptoms. Releasing obsessive thinking and acting is very important.”

In the end, all her hard work and persistence paid off. With a solid foundation set after years of disciplined eating and spiritual practice, Monet met a healer who seemed to be a hands-on miracle worker. He worked on her for two weeks straight and gave her homeopathic medicines to treat viral issues she hadn’t realized she had. The homeopathics helped her turn the corner. Later, a Filipino healer came into her life and after his hands-on healing treatment she stood up for the first time in two years. Since 2003, she has continued to work with both healers and still works with both of them today.

From 2003 on, Monet continued to rapidly progress forward. She went to Brazil and lived in The Casa de Dom Ignacio (healer John of God’s community) for one year, attending healing sessions daily and working on clearing herself spiritually. The whole time she was there, she stayed on her probiotics, cleansing and anti-pathogenic protocols.

Today, Monet has mostly recovered from CFS and FMS and her chemical sensitivities are much better, too. She can take many brief chemical exposures and feels just fine. She can function normally out in the world, but finding suitable housing that she can sleep in night after night has been more elusive. The most abnormal quality to her current life is that she’s slept outside for four years now, under a tarp outside her conventional Los Angeles home.

Monet’s advice for those recovering from environmental illness:

For MCS, I think one of the best forms of detoxification we can do is far infra red sauna. I still don’t have a home I can put it in so I haven’t done it yet, but I know that its the key as I’ve got a doctor and virtually all of her MCS clients got better with it. Also, one must stop identifying with one’s illness to step out of the box of it. It is a tricky alchemy, but is as important as physically and emotionally detoxing.”

What’s next for Monet – what does her life look like now, that life that she held a vision for all those years in bed?

Part of her life mission is to use her story, healing knowledge, and hard life lessons learned to help others. She was so badly treated by doctors, family, friends, and colleagues at different points through the worst years of her illness that she developed a strong sense of compassion for the MCS community, and a passion to help with solutions.

She is slowly getting prepared for the work ahead of her. At the moment, housing is her primary focus, as well as her art career. Her art touches on many issues common to those with MCS in its content, and so is another form of telling her story, which is also “our” story.

Her bigger dreams involve building non-toxic building complexes for the chemically sensitive. She’s in the process of networking with a team of experts to make this dream a reality, but it’s a vision that may be years away from being materialized.

We can all possibly benefit from seeing our lives as performance, or art. Art inspires, and as Monet has shown, no matter what our experience, if we use our stories to help inspire others to bring more love into their lives and to never give up hope, then we have done something important on this planet. Thank you Monet, for your bravery and indomitable spirit.

Intertwined: a narrative of art, body and healing

Julie Laffin interviews Monet Clark about her performance art work

Julie Laffin: Monet, thank you so much for agreeing to do this interview. I was very inspired by your body of work about Environmental Illness (EI) and I know others will be, too. I understand you were stricken with EI in your twenties and based on some of your visual work and writings it seems that even though you were struggling deeply with your health, you were still able to find ways to facilitate your creative expression. And given the fragile state of your health, that fact alone seems remarkable. I know several chronically ill artists who would prefer not to disclose their health status for fear of diminished career opportunities and even discrimination. Were you always so “out” about your illness?

Julie Laffin: Monet, thank you so much for agreeing to do this interview. I was very inspired by your body of work about Environmental Illness (EI) and I know others will be, too. I understand you were stricken with EI in your twenties and based on some of your visual work and writings it seems that even though you were struggling deeply with your health, you were still able to find ways to facilitate your creative expression. And given the fragile state of your health, that fact alone seems remarkable. I know several chronically ill artists who would prefer not to disclose their health status for fear of diminished career opportunities and even discrimination. Were you always so “out” about your illness?

Monet Clark: You’re welcome, it’s my pleasure. My intent for my work is that it acts as a catalyst for awakening, so thank you. I’m very pleased it moved you. I honestly, also, think it’s remarkable that I made work throughout my illness! I just kept going.

Monet Clark: You’re welcome, it’s my pleasure. My intent for my work is that it acts as a catalyst for awakening, so thank you. I’m very pleased it moved you. I honestly, also, think it’s remarkable that I made work throughout my illness! I just kept going.

I don’t make art with an audience in mind because I feel it creates a self censoring problem and brings others’ opinions and judgements into one’s art making process. So I don’t think about the audience so much or make a point to be “out”, but neither do I hide my health status. In my life in general, as well as how I present myself as an artist, I do not make a point of presenting myself as ill. I think this perpetuates the limitations box in my own consciousness, and to me, my work deals with the same themes whether I use the subject of illness or the subject of shoe obsession. So I don’t censor the illness years. I think that work is very powerful, but I don’t focus on it, either.

JL: I’m personally interested in finding ways to continue my performance work in spite of my inability to be in the public sphere due to my severe chemical intolerance. I was struck how you were able to resolve this dilemma by performing in front of a still camera and essentially addressing the camera as your audience. Using photography as a means of distributing your conceptual performances seems like a great solution. Whereas documentation of live performance art usually captures key moments of the work to later be presented as visual residue or simply a record of the performance, your still photos seem to aim to encapsulate the entire piece sometimes in a single frame that then becomes the performance work itself. Is this a correct reading of how your work functions, for example, in Performance with the Toxic Teepee?

JL: I’m personally interested in finding ways to continue my performance work in spite of my inability to be in the public sphere due to my severe chemical intolerance. I was struck how you were able to resolve this dilemma by performing in front of a still camera and essentially addressing the camera as your audience. Using photography as a means of distributing your conceptual performances seems like a great solution. Whereas documentation of live performance art usually captures key moments of the work to later be presented as visual residue or simply a record of the performance, your still photos seem to aim to encapsulate the entire piece sometimes in a single frame that then becomes the performance work itself. Is this a correct reading of how your work functions, for example, in Performance with the Toxic Teepee?

Performance with the Toxic Teepee (from the Pirate Island Performance series) © Monet Clark (click images to enlarge)

MC: Yes. However, I developed that methodology before I became ill. I’ve done my performance pieces in front of a camera since I began performance work and have rarely done performance work in front of a live audience. I was involved in the Performance/Video department at the San Francisco Art Institute and making video pieces with just oneself and the camera was very attractive to me and there was already a history of it. I find the intimacy of that process very gratifying, and the intimacy that is created is then preserved for audiences for years afterwards. I get excited just writing about it now. I love that kind of work. Framing real life events as performances came to me like a lightening bolt some years after making a lot of the pieces for still camera. I was doing that all along, but making a point to frame it that way to the audience was an epiphany that was inspiring and satisfying to me as an artist. I felt the conceptual dimensions and multitude of layers of the work were adequately brought out that way.

MC: Yes. However, I developed that methodology before I became ill. I’ve done my performance pieces in front of a camera since I began performance work and have rarely done performance work in front of a live audience. I was involved in the Performance/Video department at the San Francisco Art Institute and making video pieces with just oneself and the camera was very attractive to me and there was already a history of it. I find the intimacy of that process very gratifying, and the intimacy that is created is then preserved for audiences for years afterwards. I get excited just writing about it now. I love that kind of work. Framing real life events as performances came to me like a lightening bolt some years after making a lot of the pieces for still camera. I was doing that all along, but making a point to frame it that way to the audience was an epiphany that was inspiring and satisfying to me as an artist. I felt the conceptual dimensions and multitude of layers of the work were adequately brought out that way.

JL: The use of text in your work to inform the photography is very interesting. It extends beyond the photographic caption to become both a narrative and visual element of the piece itself. The text is displayed almost as a photographic image in tandem with the actual photos. I like how the text foregrounds the image, adding a layer of content and history to the work and offering a way for the audience to enter into the photos that might otherwise be ambiguous or harder to read in terms of being specifically about EI. How did this strategy arise?

JL: The use of text in your work to inform the photography is very interesting. It extends beyond the photographic caption to become both a narrative and visual element of the piece itself. The text is displayed almost as a photographic image in tandem with the actual photos. I like how the text foregrounds the image, adding a layer of content and history to the work and offering a way for the audience to enter into the photos that might otherwise be ambiguous or harder to read in terms of being specifically about EI. How did this strategy arise?

Pretend We’re Dead (from the Pirate Island Performance series) © Monet Clark

(click images to enlarge)

MC: What excited me the most about these specific pieces was their back story. It was also very exciting to me to be framing these stories conceptually as performance art. The work came out of the outrageous circumstances that I was living through, due to the insane housing problems that EI causes. So the text evolved organically to illustrate all of that, and I feel the text adds humor. I’ve always been a storyteller and use various forms, like with my early portraiture work. It’s just another element of what I do. I also was recently called a “populist” (a person who pits “the people” against “the elites” in a political-social context) by an art writer friend of mine. I guess it’s true, because as you say the text allows the audience to be brought into the work. I love the idea that the average person can enter my work while as the same time it holds up on a conceptual level because I think in both ways. Distilled to its essence, my work is about opposites and this theme shows up over and over in my process as well.

MC: What excited me the most about these specific pieces was their back story. It was also very exciting to me to be framing these stories conceptually as performance art. The work came out of the outrageous circumstances that I was living through, due to the insane housing problems that EI causes. So the text evolved organically to illustrate all of that, and I feel the text adds humor. I’ve always been a storyteller and use various forms, like with my early portraiture work. It’s just another element of what I do. I also was recently called a “populist” (a person who pits “the people” against “the elites” in a political-social context) by an art writer friend of mine. I guess it’s true, because as you say the text allows the audience to be brought into the work. I love the idea that the average person can enter my work while as the same time it holds up on a conceptual level because I think in both ways. Distilled to its essence, my work is about opposites and this theme shows up over and over in my process as well.

JL: Did your use of pairing images with texts arise out of a literary impulse? That is to say, are you also committed to expressing yourself as a writer and it shows up in your visual work, too?

JL: Did your use of pairing images with texts arise out of a literary impulse? That is to say, are you also committed to expressing yourself as a writer and it shows up in your visual work, too?

Pirate Island Performances intro © Monet Clark (click image to enlarge)

MC: Not really. I don’t see myself as a writer when I’m making art. I’m just interested in adding the story for those particular pieces where the story makes the pieces richer and allows the viewer to grasp the layers and conceptual dimensions of the work. However I am working on a book and a screenplay, but that’s an entirely different hat!

MC: Not really. I don’t see myself as a writer when I’m making art. I’m just interested in adding the story for those particular pieces where the story makes the pieces richer and allows the viewer to grasp the layers and conceptual dimensions of the work. However I am working on a book and a screenplay, but that’s an entirely different hat!

JL: Wow, I can imagine that it is. What sort of work were you doing before becoming ill, and how is it related to your current body of work?

JL: Wow, I can imagine that it is. What sort of work were you doing before becoming ill, and how is it related to your current body of work?

MC: Last year I began a project to digitize and organize a DVD portfolio of all my art works from the mid 80’s until now. In this process I became very clear on several themes that had been at the core of my artistic expression from the beginning, since pre-illness, which also continued through the illness years and continue in variations today.

MC: Last year I began a project to digitize and organize a DVD portfolio of all my art works from the mid 80’s until now. In this process I became very clear on several themes that had been at the core of my artistic expression from the beginning, since pre-illness, which also continued through the illness years and continue in variations today.

Poisoning/Phoenix Performance Document #1 © Monet Clark

(click image to enlarge)

I have often engaged my viewer to look at things that may be uncomfortable or taboo, that at the same time were seductive and provocative. So pointing my camera at myself when I became ill, was certainly a continuation on this theme. My work expresses the dance between opposites and how they are innately parts of the same whole: the beautiful and the horrific, eroticism and repulsion, the abject and the exalted. In esoteric circles this would be the yin and yang. One cannot exist without the other. So, there was for me, no separation from the work I did pre-illness to the work I did when the illness began in terms of themes that come up again and again. The subject matter may change, but not the underlying fascinations. I engage my audience to look at things head on, not to deny or hide that which we may prefer not to look at. In this way the act of looking becomes liberating. I’ve always done that. I’ve said my works are rituals for transmutation. They are raw, but at the same time hold a powerful intimacy. Sometimes I utilize a fascination on how women are represented in media, in art, in history and more. So utilizing myself in self-portraiture in the illness period was a continuation of my pre-illness works, and this thread persists in my most recent works.

JL: I recently enjoyed your compilation DVD and want to address one of the more recent video works, a favorite of mine you did called, Butterfly’s Shoe Fetish. In the piece you walk continuously while wearing an astonishing collection of various shoes. Knowing that you were unable to walk for years due to your disability of course informed my reading of if, but I think the pleasurable act of wearing all those beautiful shoes reads in a very powerful way for a broad audience. Because the work is very recent and seems to represent a shift in terms of the other work we’ve discussed, I wanted to ask you if this piece illustrates a new direction that you are now moving in?

JL: I recently enjoyed your compilation DVD and want to address one of the more recent video works, a favorite of mine you did called, Butterfly’s Shoe Fetish. In the piece you walk continuously while wearing an astonishing collection of various shoes. Knowing that you were unable to walk for years due to your disability of course informed my reading of if, but I think the pleasurable act of wearing all those beautiful shoes reads in a very powerful way for a broad audience. Because the work is very recent and seems to represent a shift in terms of the other work we’ve discussed, I wanted to ask you if this piece illustrates a new direction that you are now moving in?

still from Butterfly’s Shoe Fetish video © Monet Clark (click image to enlarge)

MC: Yes definitely, that piece is an exciting part of the new direction I find myself in. I’m using performance for video a lot again and I’m playing with trappings of my current life (post being wheelchair bound and bed bound). Playing with fashion is a great jumping off point for making work. I dove deeply into the fashion world after I got well enough to go out of the house again! After all that suffering and spiritual striving I really wanted to usher in the physical realm in a way that amused me. I have just relished in the senses these last several years so my new works are also a bit more flashy to the eye. The piece you describe is celebratory, because as you mentioned, I was too ill to walk in such shoes for twelve years. When I exhibit it I think it’s important that I have a statement on the wall next the piece that clues everyone in of this fact. However, like all my work there is an undercurrent. Is it really a dream come true or a nightmare? There is an obsessive quality to it. In the piece one only sees my legs and feet and shoes walking the same way each time, and it’s like these legs NEVER go away! As soon as I walk off the screen to the left in one pair I’m right back on the screen on the right in another pair. It’s meant to be shown in a never ending loop. The effect is nightmarish. And there is the soundtrack of my constant pacing that is maddening.

MC: Yes definitely, that piece is an exciting part of the new direction I find myself in. I’m using performance for video a lot again and I’m playing with trappings of my current life (post being wheelchair bound and bed bound). Playing with fashion is a great jumping off point for making work. I dove deeply into the fashion world after I got well enough to go out of the house again! After all that suffering and spiritual striving I really wanted to usher in the physical realm in a way that amused me. I have just relished in the senses these last several years so my new works are also a bit more flashy to the eye. The piece you describe is celebratory, because as you mentioned, I was too ill to walk in such shoes for twelve years. When I exhibit it I think it’s important that I have a statement on the wall next the piece that clues everyone in of this fact. However, like all my work there is an undercurrent. Is it really a dream come true or a nightmare? There is an obsessive quality to it. In the piece one only sees my legs and feet and shoes walking the same way each time, and it’s like these legs NEVER go away! As soon as I walk off the screen to the left in one pair I’m right back on the screen on the right in another pair. It’s meant to be shown in a never ending loop. The effect is nightmarish. And there is the soundtrack of my constant pacing that is maddening.

My newest piece Look Book utilizes the fashion look books as a template (where the model stands in one pose repeatedly, but in each frame wears a new outfit). In it I perform in eight outfits from my personal collection of fashion. In each frame I keep the same pose but I am not the still, emotionless model. Instead I’m highly emotional and/or vocal describing things from my life that you can’t imagine a women dressed so high-end would be doing. I’m playing with deep emotional spaces and outrageous, but true storylines. I juxtapose these with the gloss surface.

JL: Are there other artists whose work you felt an affinity with as you were struggling with your health that helped you find ways to create meaningful work in spite of being so severely health challenged? Were there any artists that inspired you to keep going even though you were so ill for two years you could not walk and were home bound, wheelchair bound and even bed bound? What got you through the tremendous difficulty of that experience and kept your desire to produce art alive when most people would have given up?

JL: Are there other artists whose work you felt an affinity with as you were struggling with your health that helped you find ways to create meaningful work in spite of being so severely health challenged? Were there any artists that inspired you to keep going even though you were so ill for two years you could not walk and were home bound, wheelchair bound and even bed bound? What got you through the tremendous difficulty of that experience and kept your desire to produce art alive when most people would have given up?

MC: I can’t think of specific artists that inspired me to keep working, but in totality I have and had been influenced and inspired by so many artists that I was just in a space where art excited me. Art was my lifeline. For instance, in the year that I was hospitalized, 2001, I just had to treat that whole nightmare as one performance art piece after another. I took self portraits with a small Polaroid camera, framing each day’s experiences as little vignettes. It was my little protest. The doctor assigned to me met with me for fifteen minutes and then declared that CFS and EI were both psychosomatic, which of course is terribly ignorant. As we know now CFS has viral underpinnings and it was revealed soon after I was released from the hospital that I had extreme arsenic and mercury poisoning. The staff tried to get me to sign papers to commit myself to Stanford’s mental ward every day and they repeatedly threatened me with involuntary commitment. It was one of the most frightening times in my life. Not only was I so near death and fighting just to stay alive, but I was fighting for my liberty as well. I was also fighting for my right to choose the treatments that I thought would get me well (which didn’t include, in my view, a trip to the mental ward). My inspiration was my desire to create something beautiful and engaging in each of the days I found myself in deplorable conditions. And my inspiration came from wanting to document those experiences. The MRI machine, for instance, was a wonderful prop for a great shot, and the image I created with it was fantastic! That is how I got through my days; with a little boost from the shot I captured that day. In this way, I was sometimes able to think more about my work, than the calamity at hand. When you’re ill, having something to do with your time that moves the energies of negative emotions is important. So that’s what kept the work coming.

MC: I can’t think of specific artists that inspired me to keep working, but in totality I have and had been influenced and inspired by so many artists that I was just in a space where art excited me. Art was my lifeline. For instance, in the year that I was hospitalized, 2001, I just had to treat that whole nightmare as one performance art piece after another. I took self portraits with a small Polaroid camera, framing each day’s experiences as little vignettes. It was my little protest. The doctor assigned to me met with me for fifteen minutes and then declared that CFS and EI were both psychosomatic, which of course is terribly ignorant. As we know now CFS has viral underpinnings and it was revealed soon after I was released from the hospital that I had extreme arsenic and mercury poisoning. The staff tried to get me to sign papers to commit myself to Stanford’s mental ward every day and they repeatedly threatened me with involuntary commitment. It was one of the most frightening times in my life. Not only was I so near death and fighting just to stay alive, but I was fighting for my liberty as well. I was also fighting for my right to choose the treatments that I thought would get me well (which didn’t include, in my view, a trip to the mental ward). My inspiration was my desire to create something beautiful and engaging in each of the days I found myself in deplorable conditions. And my inspiration came from wanting to document those experiences. The MRI machine, for instance, was a wonderful prop for a great shot, and the image I created with it was fantastic! That is how I got through my days; with a little boost from the shot I captured that day. In this way, I was sometimes able to think more about my work, than the calamity at hand. When you’re ill, having something to do with your time that moves the energies of negative emotions is important. So that’s what kept the work coming.

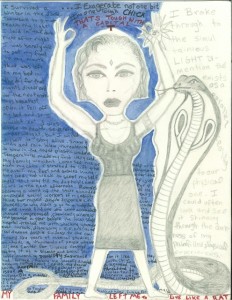

from the series Thangka, Prayer, Blessing, Incantation, Medicine, Spells © Monet Clark

(click images to enlarge)

JL: You made a body of drawings during that period that seem very explicitly autobiographical and self-revealing. They seem to be almost like journal entries, and are very powerful. Were these part of what kept you alive at the time, the ability to tell your story, share your suffering, to dream of a better future, to visualize yourself well?

JL: You made a body of drawings during that period that seem very explicitly autobiographical and self-revealing. They seem to be almost like journal entries, and are very powerful. Were these part of what kept you alive at the time, the ability to tell your story, share your suffering, to dream of a better future, to visualize yourself well?

MC: Yes all of that and more. I also thought they could be little powerful talismans for other people to look at, imbued with a potency of spiritual realization through extreme suffering. These were very mystical works in the first series and I made them with a lot of prayer that they awaken. I had been mostly alone up to that point for eleven years, so I had lost my sense of boundaries really and these works became intensely intimate. Intimacy, however, is not foreign in my other works.

MC: Yes all of that and more. I also thought they could be little powerful talismans for other people to look at, imbued with a potency of spiritual realization through extreme suffering. These were very mystical works in the first series and I made them with a lot of prayer that they awaken. I had been mostly alone up to that point for eleven years, so I had lost my sense of boundaries really and these works became intensely intimate. Intimacy, however, is not foreign in my other works.

JL: As a performance artist, your body and self image are at the core of many of your pieces. How has your relationship to your own body defined your work? Has it changed now that your health has improved?

JL: As a performance artist, your body and self image are at the core of many of your pieces. How has your relationship to your own body defined your work? Has it changed now that your health has improved?

MC: I don’t agree with the premise of the question. I feel I use subjects like the body to really get to other themes and issues, like the juxtaposition of opposites. In my performance/video piece from 1992 for instance, Convulsive Stripper, I used a silent performance where I juxtapose eroticism and power with vulnerability and repulsion. It’s as if I’m saying look at the whole spectrum of the woman, not just the image. I utilize eroticism as a lure to really look at something deeper, something uncomfortable. The convulsions and the vulnerability and intense intimacy are all there, juxtaposed with eroticism to get at the audience’s deeper discomforts and ultimately to bring them to light. So, again, the act of looking becomes liberating. The body image is an illusion – it’s not necessarily the point of my work.

MC: I don’t agree with the premise of the question. I feel I use subjects like the body to really get to other themes and issues, like the juxtaposition of opposites. In my performance/video piece from 1992 for instance, Convulsive Stripper, I used a silent performance where I juxtapose eroticism and power with vulnerability and repulsion. It’s as if I’m saying look at the whole spectrum of the woman, not just the image. I utilize eroticism as a lure to really look at something deeper, something uncomfortable. The convulsions and the vulnerability and intense intimacy are all there, juxtaposed with eroticism to get at the audience’s deeper discomforts and ultimately to bring them to light. So, again, the act of looking becomes liberating. The body image is an illusion – it’s not necessarily the point of my work.

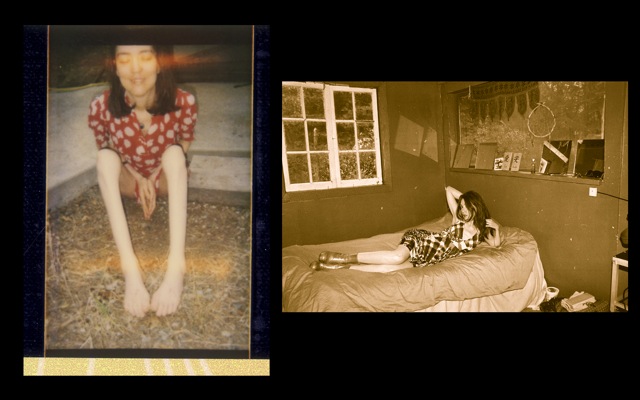

JL: The photos of you sick and skeleton-thin juxtaposed with you in a beautiful dress on a bed are very intriguing. What are you trying to say with these pieces – is it a statement about you, or a larger message about women and illness/wellness and sexuality?

JL: The photos of you sick and skeleton-thin juxtaposed with you in a beautiful dress on a bed are very intriguing. What are you trying to say with these pieces – is it a statement about you, or a larger message about women and illness/wellness and sexuality?

Poisoning/Phoenix Performance Document #4 © Monet Clark

(click image to enlarge)

MC: They are a testament to the “Phoenix” potential in us all – to rise up from our own ashes and be reborn, to start anew. They are a testament to our ability to achieve the recovery of our health. I call this work Poisoning/Phoenix Performance Documents. In this body of work, again, I frame real life events (including my real life event of being poisoned by mercury and arsenic) and this epidemic of environmental poisoning to show the impact it is having on human health. The works in this series frame, as a piece, my personal triumph in getting my health back; from looking like a holocaust survivor to looking well and even glamourous. They also frame, as a piece, the potential in all of us to get there. The images play with the theme I mentioned earlier of opposites being part of the same whole. It messes with the viewer to see an image of a beautiful, sexy, radiant woman next to an image of that same woman looking hauntingly ill and suffering. Juxtaposing these opposites is just something I do. Sexuality is a tool to get at deeper issues, not the issue itself.

MC: They are a testament to the “Phoenix” potential in us all – to rise up from our own ashes and be reborn, to start anew. They are a testament to our ability to achieve the recovery of our health. I call this work Poisoning/Phoenix Performance Documents. In this body of work, again, I frame real life events (including my real life event of being poisoned by mercury and arsenic) and this epidemic of environmental poisoning to show the impact it is having on human health. The works in this series frame, as a piece, my personal triumph in getting my health back; from looking like a holocaust survivor to looking well and even glamourous. They also frame, as a piece, the potential in all of us to get there. The images play with the theme I mentioned earlier of opposites being part of the same whole. It messes with the viewer to see an image of a beautiful, sexy, radiant woman next to an image of that same woman looking hauntingly ill and suffering. Juxtaposing these opposites is just something I do. Sexuality is a tool to get at deeper issues, not the issue itself.

JL: I understand your video work has recently been screened in the context of museum exhibitions. Are you showing work directly related to environmental illness or are you framing your work in a completely different way? Do you find that curators and art audiences are knowledgeable about and receptive to work on the subject of EI? Have you ever been in a situation where your work was delegitimized in the art world because EI is still a stigmatized condition and often an ignored conversation in the culture at large?

JL: I understand your video work has recently been screened in the context of museum exhibitions. Are you showing work directly related to environmental illness or are you framing your work in a completely different way? Do you find that curators and art audiences are knowledgeable about and receptive to work on the subject of EI? Have you ever been in a situation where your work was delegitimized in the art world because EI is still a stigmatized condition and often an ignored conversation in the culture at large?

MC: Well, again, even though there are some pretty political messages going on in some of my bodies of work pertaining to EI, the layers of meaning are far more complex to me than to just be seen as an artist working with the subject of EI or the subject of the representation of woman, for that matter. I certainly don’t present myself that way, so no, I haven’t had the experience of being rejected for it. I don’t put illness at the forefront of my work, nor my life for that matter, because it isn’t at the forefront of my work nor my life. I just make work that addresses the themes I do, and illness happens to be one of the subjects that gets to these deeper themes I explore.

MC: Well, again, even though there are some pretty political messages going on in some of my bodies of work pertaining to EI, the layers of meaning are far more complex to me than to just be seen as an artist working with the subject of EI or the subject of the representation of woman, for that matter. I certainly don’t present myself that way, so no, I haven’t had the experience of being rejected for it. I don’t put illness at the forefront of my work, nor my life for that matter, because it isn’t at the forefront of my work nor my life. I just make work that addresses the themes I do, and illness happens to be one of the subjects that gets to these deeper themes I explore.

I want to also say that in my life, I don’t avoid the subject of EI, either. If the conversation would require I mention it, I don’t hide it. I just don’t make a big issue of it or bringing people into my person struggle with it. However, if the subject does come up I no longer talk about it from a stigmatized place. I used to feel very self-conscious about it and was traumatized by people’s lack of belief that it was real. However, in working with doctors who explained how the immune system can get imbalanced and hypersensitized, etc. and also in working with EI building consultants, I feel I am armed with an easy way to articulate the condition that is believable to others. I present it based on facts and coming from a place of “of course you’ll believe me, because it’s true.” Lately, if I mention environmental illness, I’m astounded at how many people already know about it. Also, in working in the realm of non-VOC housing I feel there have been huge jumps forward in awareness of EI, even just in the last year. We are not as hidden or ignored as we once were. Public awareness is much greater than it’s ever been. We’ve hit critical mass, change is happening.

I did do an exhibition in 2008 in a live music nightclub in Hollywood where I showed nine of the Poisoning/Phoenix Performance Documents pieces. It was a show to raise money for a man in New York named George Tabb who has the 9/11 syndrome from the toxic cloud that billowed through his downtown Manhattan neighborhood after 9/11. George is amazing, and he’d been advocating for validation by the government for 9/11 syndrome. He put himself in the midst of a political storm. Senators tried to silence him. The excuse they gave was that they didn’t want the terrorists to know how badly they had hurt New York. However, we all know that illness due to being exposed to toxic fumes or particulates or water (remember Erin Brocovich) is bound to cause the “powers that be” to try and silence you. So I felt compelled to participate in that show, and make a point that countless numbers of people are getting sick from environmental poisoning. The response was very good. That work is obviously going to be looked at as work dealing with illness, even though for me it has more conceptual and spiritual dimensions that require the audience to dive beneath the surface.

JL: I know that you were homeless at one point and I imagine you were also coping with the ongoing threat being of becoming homeless a good deal of the time you were ill. I’m sure this must have been incredibly stressful and yet your Pirate Island work arose organically out of being in that precarious situation. Have you always been able to draw upon your life circumstances as an immediate means of expression? There have been times during my illness when I really did not want to make work on the subject because it was already taking up my whole life. Have you ever felt that way?

JL: I know that you were homeless at one point and I imagine you were also coping with the ongoing threat being of becoming homeless a good deal of the time you were ill. I’m sure this must have been incredibly stressful and yet your Pirate Island work arose organically out of being in that precarious situation. Have you always been able to draw upon your life circumstances as an immediate means of expression? There have been times during my illness when I really did not want to make work on the subject because it was already taking up my whole life. Have you ever felt that way?

MC: Currently I’m onto completely different subjects and it does feel great! However the emotions behind my work, and the states I achieve in performance are gong to still be driven by things I’m experiencing daily in my life and part of that is still illness. But no, the subject is not illness. And yes we do need a break, and it shouldn’t be our whole focus ever. However, I want to say honestly that those times that I spent making art were the times I had the most fun and were the most enjoyable for me. Throwing the art-making process into that mix of uncertainty and the horrible daily symptoms and experiences was a fantastic way to cope. I didn’t think about them at the time as focusing on illness, I thought of them as time to create work, yah!

MC: Currently I’m onto completely different subjects and it does feel great! However the emotions behind my work, and the states I achieve in performance are gong to still be driven by things I’m experiencing daily in my life and part of that is still illness. But no, the subject is not illness. And yes we do need a break, and it shouldn’t be our whole focus ever. However, I want to say honestly that those times that I spent making art were the times I had the most fun and were the most enjoyable for me. Throwing the art-making process into that mix of uncertainty and the horrible daily symptoms and experiences was a fantastic way to cope. I didn’t think about them at the time as focusing on illness, I thought of them as time to create work, yah!

JL: I think chronically ill artists will take a great deal of interest in your story. Is there anything you can share with them and with us that will encourage finding their own artistic voices in spite of being physically, financially, emotionally or otherwise challenged?

JL: I think chronically ill artists will take a great deal of interest in your story. Is there anything you can share with them and with us that will encourage finding their own artistic voices in spite of being physically, financially, emotionally or otherwise challenged?

MC: Thank you, in my worst years of suffering I prayed repeatedly to be a beacon of light for those coming up after me into their recoveries. So I hope that my art work, as well as my writings and my story, reaches the people that need it. My advice is to just make work. Some of the best work comes from the most low-end equipment or materials. I saw the work of an artist in South Africa who added dirt and sand to his paint to make it go further because he was so poor during Apartheid. It became his trademark, his special, unique expression and aesthetic and ultimately made him famous. The pieces were gorgeous. Sometimes those who have the most money and the best equipment and the nicest studios create work that has no soul. It’s empty. Suffering provides fertile ground for expression. Just work, find a way to express yourself and to refine your unique aesthetic and methodologies. I began the drawing series when I was too weak to hold a fork full of food and feed myself. I did a tiny bit of drawing each day until a piece got finished. Then I got stronger. Passion for your work, and continuing to work will keep the energy flowing, and it helps with all the other challenges, actually.

MC: Thank you, in my worst years of suffering I prayed repeatedly to be a beacon of light for those coming up after me into their recoveries. So I hope that my art work, as well as my writings and my story, reaches the people that need it. My advice is to just make work. Some of the best work comes from the most low-end equipment or materials. I saw the work of an artist in South Africa who added dirt and sand to his paint to make it go further because he was so poor during Apartheid. It became his trademark, his special, unique expression and aesthetic and ultimately made him famous. The pieces were gorgeous. Sometimes those who have the most money and the best equipment and the nicest studios create work that has no soul. It’s empty. Suffering provides fertile ground for expression. Just work, find a way to express yourself and to refine your unique aesthetic and methodologies. I began the drawing series when I was too weak to hold a fork full of food and feed myself. I did a tiny bit of drawing each day until a piece got finished. Then I got stronger. Passion for your work, and continuing to work will keep the energy flowing, and it helps with all the other challenges, actually.

JL: Thank you, Monet, for generously sharing your life, your amazing work and your inspiring personal story with me and the members of Planet Thrive. We wish you much continued success on your incredible path!

JL: Thank you, Monet, for generously sharing your life, your amazing work and your inspiring personal story with me and the members of Planet Thrive. We wish you much continued success on your incredible path!

Julie Genser and Julie Laffin are friends who have joined forces in their research to find people who have improved their functionality after suffering from severe chemical sensitivity. Julie Genser runs the websites PlanetThrive.com and MCSsafehomes.com. Julie Laffin is a Chicago-based performance artist currently working on transforming her work to embrace and transcend her health challenges. Both Julies are co-founders of the non-profit re|shelter, a forming 501(c)(3) organization created to address the housing crisis for those with disabling environmental intolerances.

Julie Genser and Julie Laffin are friends who have joined forces in their research to find people who have improved their functionality after suffering from severe chemical sensitivity. Julie Genser runs the websites PlanetThrive.com and MCSsafehomes.com. Julie Laffin is a Chicago-based performance artist currently working on transforming her work to embrace and transcend her health challenges. Both Julies are co-founders of the non-profit re|shelter, a forming 501(c)(3) organization created to address the housing crisis for those with disabling environmental intolerances.

You can contact Monet via her Facebook profile: http://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100000916759624.

See more of her art on her upcoming website http://www.monetclark.com (currently under construction, please check back in a few weeks…).

WOW!

Thank you so much for this powerful, inspiring piece.

I feel enlivened and lifted up just from reading it. It’s so wonderful to see what is possible.

a few parts really jumped out at me:

“Releasing trauma and fear are very important, as is faith and focusing on what progress you made, the joys in your life, and NOT the illness and the symptoms. Releasing obsessive thinking and acting is very important.”

I agree with this SO much.

and this:

“…Also, one must stop identifying with one’s illness to step out of the box of it. It is a tricky alchemy, but is as important as physically and emotionally detoxing.”

That is, indeed, a “tricky alchemy” and I think it’s so important.

With wonderful examples like Monet’s, I hope that this aspect of healing will, in time, become accepted as a critical part of healing. I really love that she also included “emotional detoxing”.

That’s something I still need to do a lot of work on and I was so inspired by the description of how negative emotions effected her when she was at her worst.

Again, thank you SO, so much for sharing this!

Libby, I knew this feature article would speak to you! So glad you enjoyed it. Thanks for sharing your favorite parts! Mine is “At her worst, near death, Monet breathed love in and out of her heart chakra” – makes me cry every time. That is SO powerful to me, I can’t stand it. Sending love through my heart chakra out to YOU ALL right now!! xxx Julie

hi ya my flower this is some full on stuff its very hard for me to see u in such a bad way its hart renching i am so happy that things are so much better for u i send my love and joyfull thoughts to u happy day

Julie I found that part so powerful too!!!

♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥

Thank you to Monet for being strong enough to let us see all your vulnerable parts. Big love!! xx

I have met Monet. The thing about truth is that when it is shown through the life of another person, we take it personally and the artist is no longer in focus. Despite that she reveals her vulnerabilities, all we see is strength. The issues she manifests as a metaphor for our toxification of the environment speak of the consequences.

She is going to be important because she stands as a poster child to the direction Capitalism is taking us. Our only cure is to go back to a healthy correspondence, as with the Indian’s to the land, which may happen as with how the Depression is getting us back to what we value most. Our responses to lessened toxifications are as a slight wheeze when we get up due to our sleeping next to synthetic carpets and linen, lead-based paints, plastic blinds, any number of artificial oxidizing elements, but for her, looking off into the resultant future, is an interrelationship of heightened numbers of cancer cases, poisonings, etc. The fact that a Stanford doctor was going to put her away in the psyche ward thinking she was psychosomatic is proof that even the best minds do not see the connection. Our lives have toxic effects. Our policies kill millions. We are delusional on so many levels. This doesn’t even begin to address the multitude of themes she addresses as an artist.

I am interested in every aspect of Monet’s message. Her example embraces so many things about our culture.

I love also how Monet never gave up on herself. Even when the world seemed to have no solutions. I also am totally inspired by how she was able to use positive visualization even during the darkest days. I myself tend towards escapism. Monet is an inspiration for those struggling with almost any issue.